Le Guin has said of the first three Earthsea books (in The Languages of the Night) that they concern male coming of age, female coming of age, and death. Presumably it was the realisation that most lives contain other things in between that prompted her to write the later books. The Tombs of Atuan has long been a favourite of mine but reading it this time I kept contrasting the male and female coming of age in the two books.

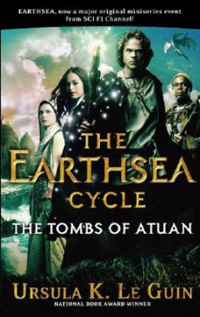

The Tombs of Atuan is about a girl who is the reincarnated One Priestess of the Nameless Powers. She lives on the Kargish island of Atuan in the Place of the Tombs, and is mistress of the Undertomb and the Labyrinth. She dances the dances of the dark of the moon before the empty throne, and she negotiates a difficult path with the other priestesses, who are adult, and adept with the ways of power. It is a world of women and girls and eunuchs and dark magic, set in a desert. A great deal of the book is set underground, and the map at the front is of the Labyrinth. It couldn’t be more different from the sea and islands of A Wizard of Earthsea.

Again, I may be too close to this book to see it clearly. When I was a child I used to play the sacrifice of Arha, putting her head on the block and a sword coming down, to be stopped at the last minute, while the priestesses chanted “She is eaten”. Sometimes I’d be Arha and sometimes I’d be everyone else, but it never failed to give me a thrill. I’m not sure what it was in this dark scene that made me re-enact it over and over, but it clearly didn’t do me any harm. It was also my first encounter with the concept of reincarnation.

We’re told at the end of A Wizard of Earthsea that this story is part of the Deed of Ged, and that one of his great adventures is how he brought back the Ring of Erreth-Akbe from the Tombs of Atuan. But the story it isn’t told from his point of view but always from Tenar’s, Arha’s, the One Priestess. She’s confident in some things and uncertain in others, she has lost her true name. I’ve always liked the way he gives her name back, and her escape, and the way she and Ged rescue each other.

What I noticed this time was how important it seemed that she was beautiful, when really that shouldn’t have mattered at all, but yet it kept being repeated over and over. Also, A Wizard of Earthsea covers Ged’s life from ten to nineteen, and at the end of the book Ged is a man in full power, having accepted his shadow he is free in the world. The text at the end describes him as a “young wizard”. The Tombs of Atuan covers Tenar’s life from five to fifteen. At the end, when she gets to Havnor with the Ring on her arm, she is described as “like a child coming home”. Tenar is constantly seen in images of childhood, and Ged in images of power. If this is female coming of age, it’s coming out of darkness into light, but not to anything. Le Guin does see this even in 1971—a lesser writer would have finished the book with the earthquake that destroys the Place and the triumphant escape. The final chapters covering their escape through the mountains and Tenar’s questioning the possibilities of what she can be do a lot to ground it.

This is also beautifully written, but it isn’t told like a legend. We are straightforwardly right behind Tenar’s shoulder the entire time. If we know it’s part of a legend, it’s because we’ve read the first book. There’s none of the expectation of a reader within the world, though she never looks outside it. Earthsea itself is as solid and well rooted as ever—we saw the Terranon in the first volume, here we have the Powers of the tombs, dark powers specific to places on islands, contrasted to the bright dragons flying above the West Reach and the magic of naming.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published eight novels, most recently Half a Crown and Lifelode, and two poetry collections. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here regularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal where the food and books are more varied.